by Taylor McConnell During 1943, Patrol Bomber Squadron VP-206 (later VPB-206) was stationed at Coco Solo Naval Air Station, Panama. Flying Martin “Mariner” PBM-3s’s, we were engaged in tracking down German U-boats in the Caribbean. But part of the Squadron was deployed to an advanced base in Corinto, Nicaragua, on the Pacific Coast. From there

by Taylor McConnell

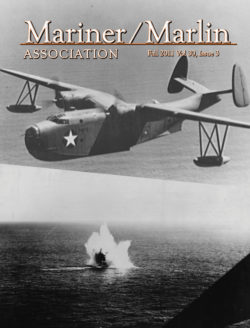

A Consolidated PB2Y-2 Coronado, a large flying boat patrol bomber designed by Consolidated Aircraft 1937, in flight. The plane was operated by patrol squadron VP-13 (aircraft 13-P-1). (http://en.wikipedia.org/)

During 1943, Patrol Bomber Squadron VP-206 (later VPB-206) was stationed at Coco Solo Naval Air Station, Panama. Flying Martin “Mariner” PBM-3s’s, we were engaged in tracking down German U-boats in the Caribbean.

But part of the Squadron was deployed to an advanced base in Corinto, Nicaragua, on the Pacific Coast. From there they flew eight flights daily to and from the Galapagos Islands on the Equator (four planes each direction). This was part of the outer defense perimeter of the Panama Canal, designed to provide early warning of a Japanese attack on the Canal. In 1943 there was still a possibility that such an attack might be mounted.

I was assigned to this duty in early October, the third pilot for these long-distance flights. On October twentieth a small hurricane was churning across the Caribbean toward the eastern coasts of Nicaragua and Honduras. I suppose it was what we today would call a “category one” hurricane.

A PB2Y “Coronado” carrying some 20 passengers and crew was flying from the States to Panama. In those days long before weather satellites, the tracking of hurricanes was quite imprecise. So the PB2Y flew into that hurricane and was downed at sea.

Since we were the nearest squadron to this event, we were ordered to set up a search-and-rescue mission. On the morning of October 21, the seven planes available at Corinto took off on this mission.

Flying to the northeast, we crossed the 264 miles to the northern coast of Honduras. We took up stations every three miles, North and South along 8600 degrees west longitude and 1657 to 1715 North Latitude. This spaced our planes three miles apart as we flew east and west, and at the end of each East-West leg, we would fly 21 miles south and then reverse course. This created our search grid.

But! — We were flying right into the teeth of that hurricane. One of the most impossible ventures we would ever engage in.

As the junior pilot on PBM-3s #6697, I was expected to do the navigating. Lt. J. G.’s James (Jim) Hobgood and John (J.P.) Morgan were my seniors; both qualified patrol plane commanders, with Jim in the left seat that day.

Years later, J.P. and I exchanged correspondence and then personally visited at length about that day. My memory is that of a navigator’s nightmare. Flying low, at 500 feet, so we could spot life rafts, in and out of clouds, and overseas that were running 25 to 30 feet of mostly white water. Mercilessly pounded, I had to recalculate our drift and groundspeed every few minutes. Why? We were so close to the center of the hurricane that the wind direction was constantly shifting. The plane was wildly pitching, yawing and rolling.

Let J.P. take up the story, from a pilot’s perspective. He wrote: “My first image is that when we arrived on station the drift was forty-five degrees! Intuition as well as math tells you instantly that if your air speed is 120 knots you are obviously in a 120 knot crosswind!” This was of course a gross exaggeration–but it surely seemed that bad!, even though we calculated it at 80 knots.

J. P. Continues: “ The second image: as you say, 25 foot seas, “Even higher”? And the third image: all at once the crosswind ends, the sea is less angry, some sunlight shines through. What is going on? I hadn’t previously learned the anatomy of a hurricane in any detail.

“The fourth image: after about a minute of calm, the crosswind is now 80 knots in the opposite direction!”

Let me add another image: at one wild moment we saw another PBM suddenly pop out from cloud and cross our bows not more than 200 yards away. Dead-reckoning navigation was obviously ludicrous, but what else did we have? Celestial navigation was impossible, there was no radio or radar navigation, and Loran and GPS had yet to be invented.

We finished the search assignment after about six hours and proceeded to retrace our flight across the Isthmus to Corinto. By now the hurricane had reached the mainland. Let J.P. take up the story again:

“When the time arrived to return to Corinto, we remained over water and went into a spiral climb to over 12,000 feet, because the chart showed mountains of 11,000 feet. Controlling the plane was fiendishly difficult. When these high winds hit a mountainside, the updrafts are formidable.”

[And the downdrafts and cross-currents can suck you into canyons. ]

“After we leveled off we headed southwest, flying at high power settings. Even so, it was a struggle to keep the wings and nose level. At one point we were nose-high according to the artificial horizon and the air-speed was dropping. Jim was pushing on the yoke and he ‘invited’ me to help and we both pushed and pulled on the yoke with all our might. A pattern was set of our wrestling the yoke using our combined strength.”

[PBM’s had no power assist for the controls.]

“On occasion, it required all our strength combined to avoid stalling in a downdraft. Jim had been flying needle-ball-airspeed, and I pointed out that with the artificial horizon there is no time lag in reporting the attitude of the airplane.” (In the clouds most of the time, there was no real horizon to use.) “I have remembered such detail because we were all quite close to death that day and I have relived it over and over…

“I still remember the immense relief, seeing the Pacific Ocean appear below us through a hole.” (I had commented to J.P. that they dived that PBM into the hole in a steeper spiral than I believed the plane could take.) J.P. replied, “I don’t disagree, but my strong memory is that of extreme caution in not allowing the cylinder head temperature to go below the proper limit for fear of the engines seizing.”

Six of the seven planes made it back to base, and the seventh landed on Lake Managua. And that evening, the thought that was haunting our conversations was “Will we have to do this again tomorrow?” The planes themselves provided the answer: popped rivets and frayed control cables said they were not safely flyable. Several planes had lost their artificial horizons, even though the reliable old turn-and-bank indicators were still functioning.

What about the passengers and crew of the “Coronado”. Only two survived, washed up on tiny Swan Island, about 100 miles from the Honduran coast. I marvel at how any life raft could live in those seas we flew over!

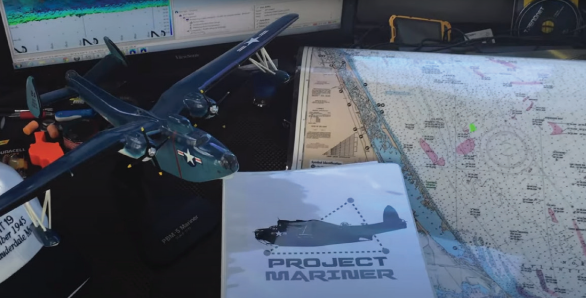

More articles are found in the Fall 2011 MMA Newsletter.

More articles are found in the Fall 2011 MMA Newsletter.

Hurricane Flying / Taylor McConnell

First Patrol Over the South China Sea / Harry E. Belflower,

It’s wearisome, but Air Patrols Vital – To Interdict Foe’s Seaborne Supplies / Don Dedera, Arizona Republic, April 4, 1966

PBM Vs. Nazi Sub – 1943 /Dudley C. Holbrook, VP-204

MMA 30th Reunion Information

Annual membership in the Mariner/Marlin Association entitles members to receive four issues of the Newsletter.

Click here to find out how to become a member.

5. Letters

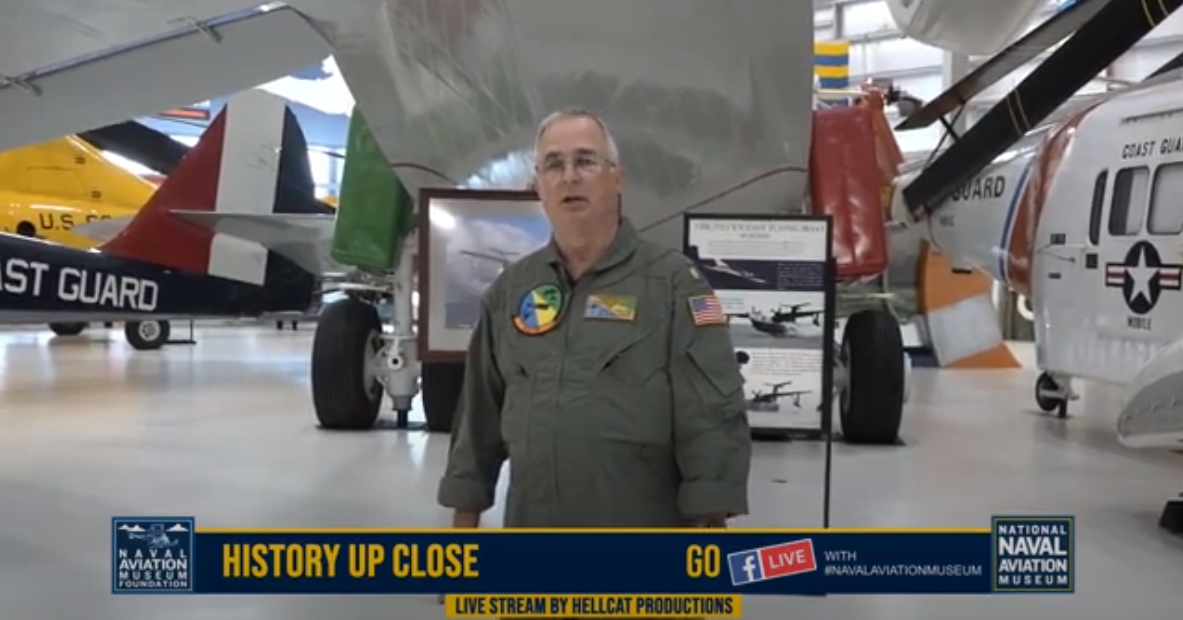

6. Note From the President

Doug Miles

6. From The Editor

Arnold Zaharia

7 Hurricane Flying

by Taylor McConnell

9 First Patrol Over the South China Sea

by Harry E. Belflower,

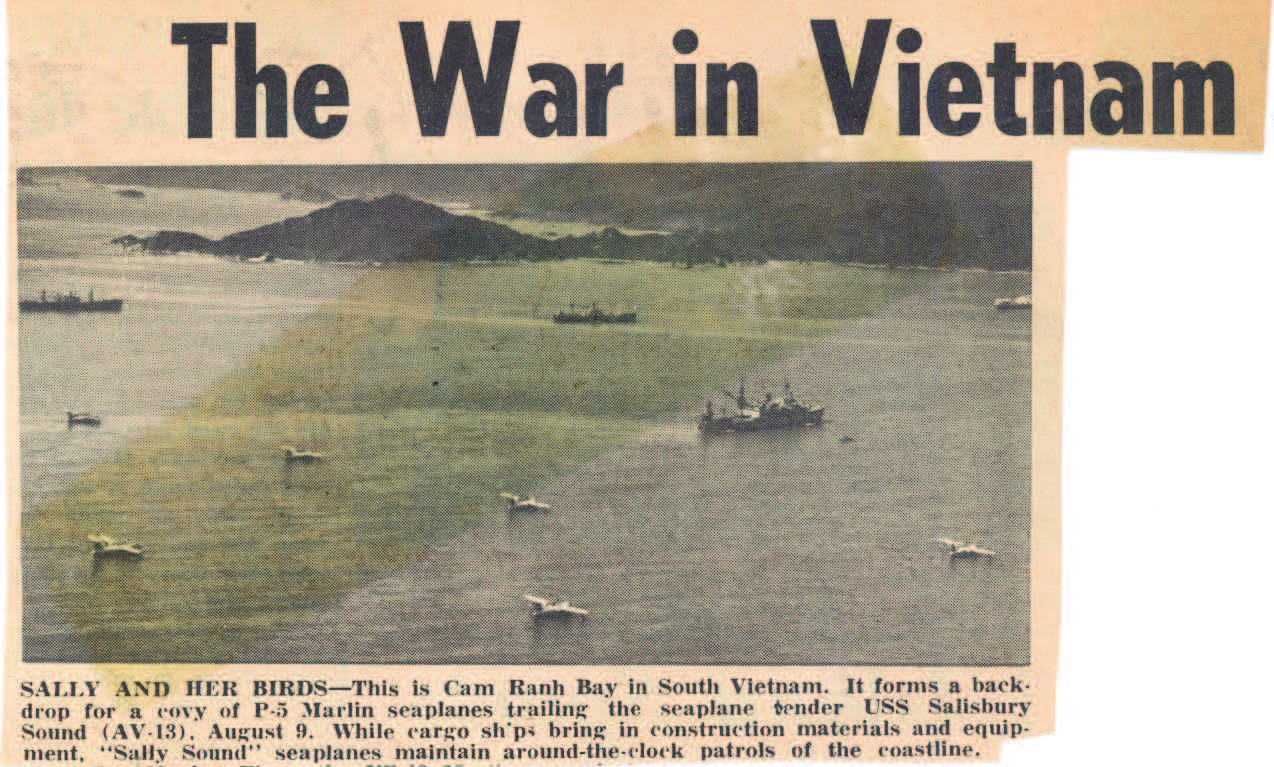

12 It’s wearisome, but Air Patrols Vital To Interdict Foe’s Seaborne Supplies

By Don Dedera, Arizona Republic, April 4, 1966

14 PBM Vs. Nazi Sub – 1943

By Dudley C. Holbrook, VP-204

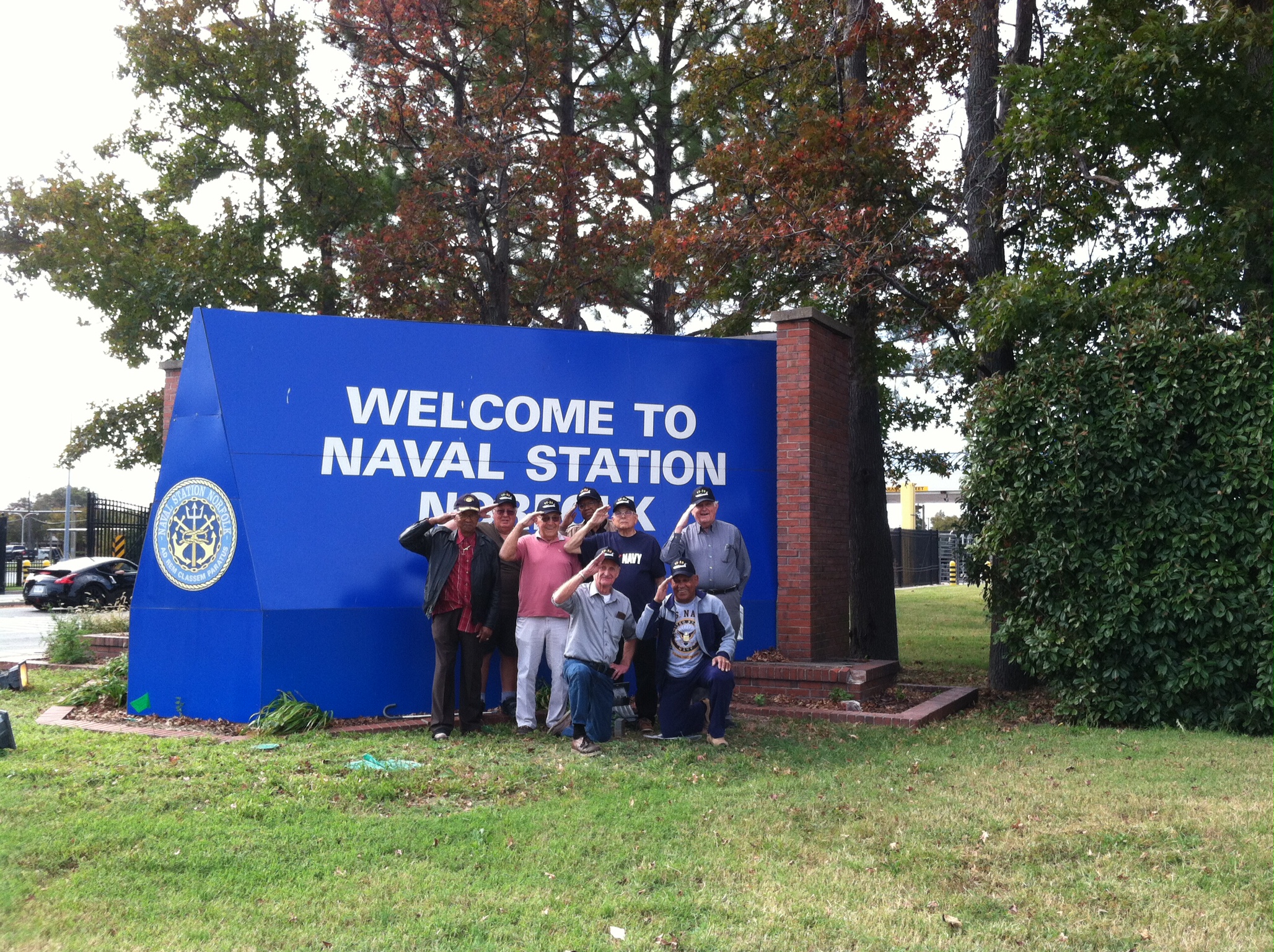

23 MMA 30th Reunion Information

2 Comments

Gene Toffolo

July 12, 2014, 06:21Would you be interested in a 3 ring binder cruise book for VPB 204? It has pictures form air crew training, Corpus Christi TX 1945 & Panama, Cuba, Bermuda 1946.

REPLYJewel

April 5, 2016, 11:16Addressinjg all the nuances of email advertising, snail mail

REPLYadvertising, content material marketinjg by blogs, and distribution by way oof social media retailers

like Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and (particularly) Google+.