by CDR Charles H. Zilch, USN (Ret), Stanton, MI The old saying “practice makes perfect” certainly applies to the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. Shortly after our second tour to WESTPAC with Task Force 77 began we lost two A-1H (Douglas Skyraiders) just east of Hawaii and successfully rescued the pilots. Sadly, my wingman suffered

by CDR Charles H. Zilch, USN (Ret), Stanton, MI

The old saying “practice makes perfect” certainly applies to the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps.

Shortly after our second tour to WESTPAC with Task Force 77 began we lost two A-1H (Douglas Skyraiders) just east of Hawaii and successfully rescued the pilots. Sadly, my wingman suffered a broken back, which ended his flying career.

Telling their story around the ready room, we discovered that roughly half our second tour pilots had ditched in the Pacific Ocean. This resulted in a special patch unique to pilots who had pilots who had ditched. Now, we joke at happy hour about these events, but at the time they were anything but funny.

On 21 August 1951, we were flying south of Norfolk, VA, on a Navy bombing range, practicing low-level skip bombing. Pass after boring pass we rolled in, made the radar approach to the range, and dropped practice bombs.

I had been flying from the left seat and went aft to wait while the junior pilots qualified. After several passes and some very rough flying (pilot technique), the dreaded news was heard on the intercom.

“Our right aileron is missing!”

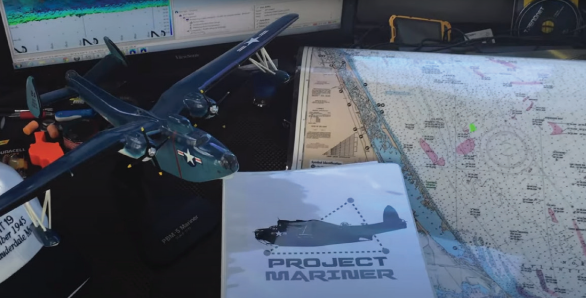

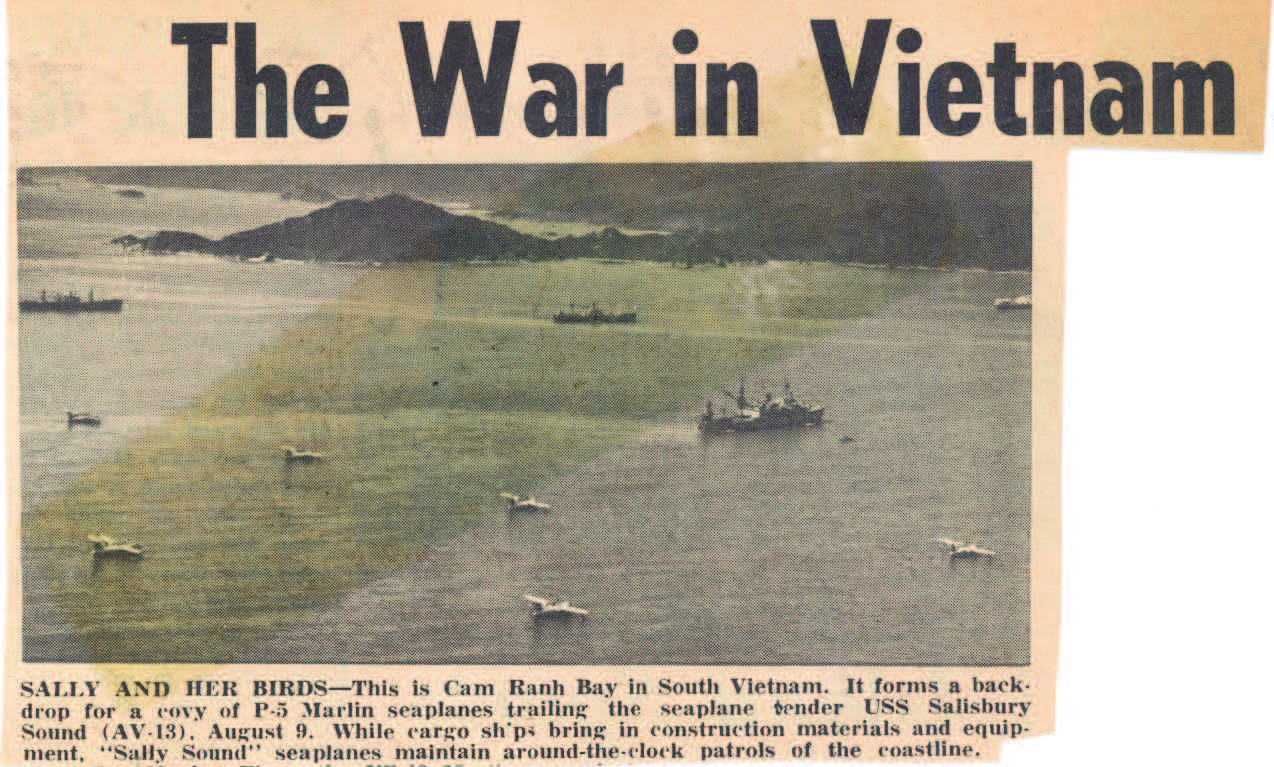

Actually, it was hanging loose. Now, the fun began. What to do? I hurried to the cockpit and resumed flying the P-boat – the PBM-5 Martin Mariner, a twin-engine long-range seaplane bomber.

We climbed to 6,000 feet and headed north, fully expecting to lose our right wing.

We offered the crew a chance to bail out with rescue highly likely. Nobody volunteered. By that time we were 30-plus miles north of our seaplane base at NAS, Norfolk. Atlantic Fleet Headquarters had been alerted and Navy Aircraft were all around us like a mother hen around her baby chicks.

Keeping our wings level by only using our rudders, we set up a rate of descent for touch down with the airspeed 80-90 knots. Stall speed that weight with flaps down was somewhere around 60 knots.

As we got close to the waters of the northern Chesapeake Bay, we could see the waves were roughly six to 10 feet high – not an ideal landing situation. Our initial touchdown was literally perfect and we smashed headlong into the first wave without damage and not quite zero forward speed.

The final challenge was a 4 1/2-hour, 45-mile taxi in open seas to Norfolk. We were escorted by U.S. Coast Guard craft, in case we sank and needed water rescue. Jokes flew about the airplane qualifying as surface wave Officer of Deck Underway.

We had a great deal to be thankful for that day, and since we landed safely with no injuries or material damage, that flight was not classified as an accident. Just another tribute to the superior training provided by the U.S. Navy and Marine Corp to its aircrews.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *