Submitted by Dave Rinehart Never let it be said shanghaiing was not practiced by the US Navy in the 1950’s! My only personal involvement with this practice began on Oct 1, 1953. I was in Crew 5 of Patrol Squadron 50 deployed to NAS Iwakuni, Japan. We mustered as usual at 0800 in the hanger

Submitted by Dave Rinehart

Never let it be said shanghaiing was not practiced by the US Navy in the 1950’s! My only personal involvement with this practice began on Oct 1, 1953. I was in Crew 5 of Patrol Squadron 50 deployed to NAS Iwakuni, Japan. We mustered as usual at 0800 in the hanger area down by the seaplane ramp. Following muster we were treated to the monthly payday and I recall taking out about $110 in military payment script. More about my money later.

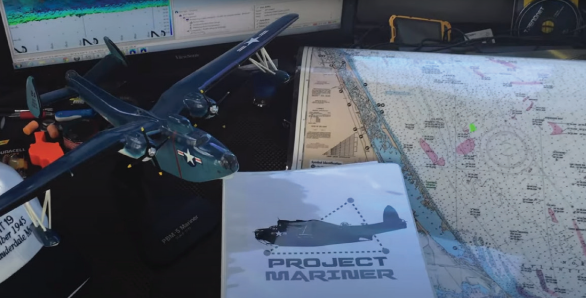

VP-50 had 12 PBM Martin Mariner flying boats and 12 flight crews. These aircraft were getting a little long in the tooth, the type having performed all through WWII after being first flown in 1939. Very few aircraft flew operationally both during WWII and a couple of years past the Korean War like PBMs. Our planes were pure flying boats, meaning no landing gear, so we had to operate strictly from water. The PBM only had 2 engines but they were R-2800s rated at 2100 h. p. each. Their 118 foot wingspan was greater than its contemporaries, the famous B-17 and B-24 four engine bombers. Our patrol weight was upwards of 50,000 pounds which required the use of 4 JATO bottles to get airborne.

Back to the day in question, we crewmen were just hanging around waiting for all of our crew to be paid and to learn what our work assignment would be that day (we were not scheduled to fly) from our Plane Captain, John Price AD1. Our crew was scheduled for liberty after noon chow. It was not to be as John soon cornered Charley Fix AO3, Ray Cook ADAN and me, Rinehart AT3, to stand the watch on 9 boat since its crew had not yet returned from R & R. We moaned and groaned since this meant 24 hours on the plane tied to a buoy outside the breakwater and no liberty tonight. No amount of complaining would sway good ole John.

Since the seaplane ramp at Iwakuni could only accommodate about 6 planes on a paved surface, this meant that the other 6 had to be flying or secured to a buoy outside the breakwater. Buoy watches were stood by 3 enlisted men generally from about 0900 until the same time the following day, as long as a plane was on a buoy. These watches were very boring as there was nothing to do but talk, smoke, read or sleep. One crewman had to be awake at all times and we generally split the night into three 3 hour watches, 2100 to 2400, then to 0300 and finally to 0600.

The Navy certainly took care of us in the chow category. Some time each morning a bowser boat would come alongside and give us large boxes of food for the 9 total meals we would need during the next 24 hours. It was all ‘unprepared rations’ as were the flight rations when flying. Part of the time on the buoy was spent in preparing our meals. But it was a lot easier to cook for 3 than it was an entire flight crew of 12 to 13 men plus an occasional extra man. Our patrols lasted anywhere from 9 to 12 hours and we were given either 15 breakfasts and 15 dinners or 15 suppers and 15 breakfasts, all unprepared.

Our squadron had 12 flight crews and each was comprised of 3 or 4 officers, all pilots in those days, no NFOs or TACCOS, and nine enlisted. There would be 3 mechs (ADs – Aviation Machinist Mates), one of which was always the Plane Captain, 2 ordnancemen, (AOs -Aviation Ordnancemen) and 4 electronics types (generally 2 Aviation Electronicsmen, Als and 2 Aviation Electronics Technicians, ATs). Generally the enlisted were all ‘rated’ (petty officers, but not always). The pilots would consist of a Patrol Plane Commander, PPC, Patrol Plane 1st Pilot, PP1 P and 1 or 2 Patrol Plane 2nd Pilots, PP2Ps. The latter would be relegated to navigational duties and seldom get flying time in the cockpit.

We were soon taken out to 9 boat, BuNo 84713, where we relieved the crew who had spent the previous 24 hours there. We settled into the routine of talking, sleeping and preparing our meals.

Most of us would spend our night watches in the most comfortable seats in the aircraft, the cockpit. We had to keep a sharp eye on the tender for any kind of a signal, generally flashing lights. We would disconnect the intercom system and tune our BC-348 radio receiver to the Armed Forces Network radio station to listen to music while on watch. Disconnecting the intercom would not drain the batteries as fast as otherwise. Our aircraft contained an auxiliary power unit (APU) that generated electricity for the galley stove, lights and especially to provide starting power for the main engines. Invariably, using the powerful radio receiver would cause the 28 volt batteries to drop to about 19 or 20 volts sometime after 0300. If the voltage dropped too far, we wouldn’t be able to start the APU using battery power. Thus, the APU would have to be started to recharge the batteries. This engine was very loud and was located on metal decking right above the bunk area. At this time in the morning, the other 2 crewmen would be trying to sleep but that would be impossible when the APU was running. Thus, most crewmen wanted the 0300 to 0600 watch since they would not be able to sleep anyway.

At approximately 0535 hours the next morning, Oct 2, we felt and heard a boat pulling alongside, then a flight crew jumping aboard. It turned out to be a partial flight crew. It seems Crew 3 was scheduled for a patrol on 9 boat but 3 members of Crew 3’s enlisted had not returned from their R & R leave. Guess who had to fill in for the missing men? We, the buoy watch, and that’s when we were shanghaied! We three from Crew 5 were not happy about having to stand an almost 24 hour watch on another crew’s aircraft then having to fly a long patrol with yet another crew! But there was nothing we could do about it. There were now 14 men aboard ‘9 Boat’, ten from Crew 3, three from our Crew 5 and one Photographers Mate, Nelson PH3. It was not unusual to carry a photomate but such was not a normal practice.

Digressing for a moment, here’s a little history. Navy Patrol Squadron 50 had recently arrived at NAS Iwakuni, Japan for its approximate 6 month deployment. This arrival occurred in late May, 1953, some 2 months prior to the Korean War cease fire. We were ‘home-ported’ at NAS Alameda, CA Our pattern of patrols which included the coastlines of Korea, China and a little bit of Siberia began immediately since the squadron we were relieving, VP-47, was anxious to return to CONUS.

Back to the shanghaiing! We began getting ready to get airborne by starting the engines off of the APU. As soon as we had one engine running, the PPC (Patrol Plane Commander), Lt M. N.

“Moe” Hansen ordered the man in the bow to cast off from the buoy. Immediately the other engine was started and we began water taxiing around to warm up the engines. Soon, Mr. Hansen began the magneto checks by running each engine in turn up to 2200 RPMs and switching the magnetos from “BOTH” to “L” , then “BOTH” to “R” and watching to see how much of an RPM drop occurred. If not over 100 RPMs, that engine was deemed OK. Several other checks were made as well. We buttoned up the aircraft and taxied to the duty sea lane. We took off at 0548.

To digress again, there were several reasons for these patrols. We were primarily tasked with the job of watching for any enemy (North Korean) naval vessels. They could be attempting to land infiltrators below the DMZ, laying mines, etc. Rarely did we encounter enemy vessels but we often came across merchant vessels heading to or from mainland Chinese ports. Since we were primarily an anti-submarine squadron, we also had to be alert for any Russian subs that could enter the war, especially by attacking our Task Force 77 in the Sea of Japan. We provided ASW protection most night time hours around TF 77. Another mission was to look for any amphibious buildup by either the Chinese Communists or the National Chinese. Both had threatened to invade the other after the Nationalists had fled to Formosa (Taiwan) circa 1949. US national policy at that time stated that it would not be in our best interest to allow either of the Chinese governments to invade the other’s territory. Weather reporting was another task since much of the Korean weather that could affect our military in Korea first transited the Yellow Sea which was heavily patrolled by Navy patrol aircraft. A rather brief task early in the war was the machine gunning and detonating of floating mines that posed a threat to our surface Navy. We even utilized radar photography when heading directly toward mainland Chinese cities for possible future use in attacking them with atomic weapon armed Navy aircraft. Finally, we engaged in ECM (Electronic Counter Measures- passive} to locate and analyze Communist Chinese radars.

All of the foregoing pertained to our missions prior to the Korean War armistice but some applied afterward. Since this patrol occurred some 2 months following the Korean armistice (July 27, 1953}, our missions remained pretty much the same. The following quote is from a statement from ComNavFe as to how the armistice would affect us and I quote:

“5. The following comments from ComNavFe are considered pertinent to all hands:

a. An armistice is only a suspension of fighting until a political conference smoothes the way to peaceful settlement.

b. The job will not be finished until there is a political settlement.

c. We must maintain the same readiness for combat that we now have, not relax our guard, and remain alert and fit.

d. Present rotation policies will remain in effect until further notice. The above statements emphasize the need for continued readiness, and this command will support the indicated action 100% in performance of duty and in spirit.”

Our patrols carried various names, like Fox Blue, Fox Grey, Tsushima Strait, Weather 77, 95.1.1, Able and Fox Red. We were slated for the latter on this flight and the patrol track was from our base on the southern part of Honshu Island and then pretty much straight toward Lianyungang, China. We would transit the Shimonoseki Strait, then across the Korea Strait south of Cheju Do Island and on toward mainland China, a distance of about 600 miles. Upon reaching a point of some distance off the Chinese coast, we would turn N toward the Shantung Peninsula. Our orders were to avoid approaching closer than 3 miles in order to remain in international waters. This differed from the Communistic countries which held that the limit should be 12 miles rather than 3.

At some time either before we turned northward or soon afterward, we began closing on radar contacts to determine what they might be. Along the Chinese mainland coast these contacts were most often merchant ships, generally British flagged, either on their way to or from a Chinese port. Most of the time, these ports were either Shanghai or Tsingtao. I always thought it interesting that up until the armistice British ships were trading with the Chinese Communists at the same time British soldiers were fighting Chinese Communists a short distance away in Korea.

When spotting a surface target on our radar, APS-31, we would home in on it. We would pick up these ships perhaps 30 miles away, depending on their size and our altitude. We generally flew about at an altitude of 1000 feet so we could descend easily when making passes on them to photograph and RIG them. To RIG was an acronym meaning to Recognize, Identify and other aspects I have forgotten. We did not always have a camera but we would determine the type of bow, sequence of kingposts, masts and funnels and the type of stern. Of course we would note the ship’s location, heading, speed and if it carried any deck cargo. I would venture the high percentage of the ships we encountered were British. Seldom could we read the name of the vessel but we could ID it by type, i.e. Fox Able, Fox Baker, etc.

On this patrol we were lucky to have a Photographers Mate aboard. He would position himself in the after station where we had approximately 4’ by 4’ hatches that would open to allow him to photo the ship. We would make a pass, or passes, at about 300 feet of altitude to get a good broadside shot. I have often wondered what happened to the 1 000’s of pictures and descriptions that were acquired in those days!

An interesting sidelight to this patrol was unknown to me for many years. Seldom did the enlisted members of a flight crew receive any type of pre-flight briefing but the pilots did. It seems there was a British merchantman that was transiting the Chinese coast on a northerly course some days prior to our patrol. It carried a load of lumber as deck cargo and this attracted the attention of some Nationalist Chinese soldiers who boarded and commandeered the vessel. The vessel’s name was the SS Admiral Hardy. The Nationalist Chinese forced it into a port somewhere in the Formosa Strait and off loaded some of the lumber, an act of piracy on the high seas! The vessel was turned loose to proceed northward on its regular course when some how the Captain turned up missing. There was no contact with this ship for some time and the British authorities asked the US Navy for help in locating it. One of our missions on this Oct 2 flight was to be on the lookout for the SS Admiral Hardy.

At approximately 1140 hours I was manning the radar which I had been since about 1000 hours. We were heading 330 degrees and I had two targets on my radar screen, one at 14 miles, 45 degrees port and the other 19 miles 40 degrees port. Using the radar I homed us in on the first target which was a ship. The second target was a small island named T’sang Chou Tao. We soon dropped down to about 300’ or so to make our RIGGING and photo passes. At some point I recall telling Mr. Hansen we were only 2 and ½ miles from the island off our port bow. My intent was to let him know we were within 3 miles of that island, a territorial violation if it was Chinese and I’m sure it was. He acknowledged this but didn’t seem too concerned.

It was almost 1200 hours when we finished checking this ship, which turned out to be the SS Admiral Hardy, inbound for Tsingtao. We were climbing back to our patrol altitude and I had just stood up from the radar operator’s seat to allow Smiley, AT3, from crew 3 to relieve me. Suddenly there was the sound of what sounded like tearing sheet metal from atop the flight deck. I looked up and saw nothing unusual but did notice the co-pilot, Ens. P. J. Rutan in the right hand cockpit seat looking back over his right shoulder and I knew we were being fired upon! Its strange that I knew what that sound was even though I had never heard it before. I was sure it was shot from an attacking aircraft passing overhead.

The best defensive position in a PBM, as in most aircraft, from attacking planes was our tail turret which held twin .50 caliber machine guns. I remember thinking I should go there but B. J. McGill ADAN had just been relieved on the flight engineer’s panel and he also headed aft, ahead of me, direct to the tail turret.

I believe we both hollered at 3 other crewmen lying down in the bunkroom that we were being attacked as we passed through that compartment. Fisher, our photomate, was still in the after station when I arrived there. My thought was to man one of the two .50 caliber machine guns stowed there that could be fired broadside. I grabbed a headset and as soon as I put it on I could hear Mr. Hansen literally screaming for us to get the guns loaded. We were diving for the deck

(water) at this time and we leveled off at about 300 feet altitude. I soon had my gun secured to the hatch sill and the link chute with the ammo belt fed up to the gun. Just as I was charging the weapon, I saw a large pattern of splashes in the water about 100 feet abeam of our port waist. A second or two after these splashes appeared, a very shiny plane flashed by on the port side level with us. This aircraft was obviously a MiG-15 and it was really moving! These MiGs were easily identifiable even though I had never seen one before. It was turning left to circle around for another firing pass. The shell splashes must have been 23mm cannon fire since the MiG’s armament consisted of two 23mm machine guns and one 37 mm cannon. I had seen a lot of .50 caliber machine gun fire in the water during our air to surface machine gun training and the splashes I saw that day were considerably larger than our .50 caliber gun splashes. Just as the MiG passed us, Nelson, PH3, was ready with his K-25 aerial camera which he raised, aimed and immediately snapped the shutter. We learned later that he didn’t get a picture.

Our PBM-5S2s were armed with six .50 caliber M2 Browning machine guns, 2 in each of the bow and tail turrets and the two single guns in the after station. Although we had ammunition aboard, none of it was actually fed up to the various guns in the plane, but stored in ammo boxes near each gun turret or station. Then it was necessary to feed the ammo belt down through the link chute, raise the receiver cover and insert the ammo belt into the receiver. To arm this weapon one had to pull the arming lever rearward twice, which I did, then to test fire the gun. I pulled the trigger and nothing happened. By this time, Charley Fix, AO3, was doing the same thing to the starboard gun so I hollered at him to switch places with me because he would know how to arm the port gun. At some point in all of this, one of us called the flight engineer on the intercom to give us ‘gun power’. These waist single .50s were hydraulically powered, just like the turrets, to combat the slipstream. There is a switch on the flight engineers panel that turns on the power to each gun and turret. One might think the flight engineer would have done this automatically, but we later learned that Smitty (Smith, AD2) the flight engineer who had relieved Billy McGill AN had been busy. One of the things he had to do which everyone else had overlooked was to purge air from the hull tanks. On a PBM, most of the avgas was carried in 7 large fuel tanks in the hull which held a total of 2200 gallons. This gas was periodically pumped up to the wing service tanks, one in each wing of 250 gallons each, from which fuel was pumped to the engines. One of the greatest dangers to aircraft being attacked would be a shell, especially an incendiary, puncturing a fuel tank filled with gasoline vapor. Our plane had a system that allowed CO2 to fill the air spaces inside the hull fuel tanks to make them less likely to explode if penetrated. Smitty had left the flight deck to go down on the main deck to initiate this CO2 purging system.

In the meantime, Ray Cook ADAN, the third member of my crew had appeared in the after station and we sent him back into the ‘tunnel’ to move the ammo belt from the storage boxes aft on the roller tracks to the tail turret. The man in the tail turret had no way to do this. The bulk of that turret’s ammo was stored in boxes attached to the ‘tunnel’ bulkheads some distance forward for weight and balance purposes.

Consider this scenario. Here were 2 heavily armed jet fighter aircraft attacking a slow, cumbersome flying boat flying straight, but climbing, with no forewarning. We had no lookouts posted as it was after the Korean Armistice, and certainly didn’t expect this kind of a reception some 30 miles off the Chinese coast. We were still climbing out to our patrol altitude of 1000’ when jumped. Thus our airspeed was probably about 110 knots. What were the odds of surviving this?

During the time Charlie and I were trying to load our guns, whenever a MiG would start a firing pass, Billy McGill in the tail turret would notify Mr. Hansen as to which side the MiG was approaching and Mr. Hansen would immediately throw our plane into a steep turning bank, somewhere between 60 and 90 degrees, toward that side. This had the effect of throwing off the MiG’s pursuit curve and undoubtedly saved our bacon. I recall that at various times, Charley and I were either looking straight down at the water, perhaps some 200 feet below us, or looking straight up into the sky. PBMs were equipped with safety belts for the afterstation gunners for this contingency but we did not have time to look for them. Mr. Hansen continued screaming into the intercom to “Get those guns firing”, repeatedly. Believe me, we were trying!

It’s interesting what goes through one’s mind during a stressful situation such as this. I recall thinking we would be shot down because we were being attacked by 2 jet fighters with heavy caliber guns and we were merely a huge, slow flying boat armed with only .50 caliber machine guns. Our cruising airspeed was around 115 but I suspect we were turning about 170 knots while being attacked, certainly not fast enough to escape jet fighters! I thought of the $110 in military script I had in my billfold. A rather large amount for an AT3 in those days but I drew it out to buy a Zenith Oceanographic short wave radio from the ship’s store in Iwakuni. I recall thinking during the attack we will be shot down and float around in a life raft for some time and I would lose this money. I wished I could have sent it home so my parents would have it and make use of it. Several years later, I heard that during the attack, our PPC, Lt. Hansen, was thinking that we would be shot down, captured and he would be paraded though the streets of Shanghai in a bamboo basket! Ah, the optimism of youth. Neither of us thought we would be killed.

I continued the loading and arming of the starboard gun as did Charley the port one. I tried my gun; it fired, and almost immediately I looked aft to see a MiG beginning his pursuit curve toward us to make another, I presume, firing pass. Since this was not our plane, we could not find the

‘sight leads’ that provided electrical power to the illuminated sights for these waist guns. They were stored somewhere but we didn’t have time to conduct a search for them either. I merely pointed my gun toward the MiG as best I could and held the trigger bar down. I got off about 20 rounds when the MiG, perhaps upon seeing my shot coming toward him, broke off the pass and turned to his starboard. I do not believe I was successful in hitting the MiG. It did not return fire then.

When I had moved to the starboard gun was when I first noticed the damage from a 37MM cannon shell that had hit our starboard vertical stabilizer. From my vantage point, the hole appeared to be over a foot in diameter with many smaller holes all around it. Once the MiG I saw departed the area, I saw no more ‘enemy’ aircraft, so they must have left. But they had been firing at us for about 15 minutes. Soon, Mr. Hansen our PPC appeared in the afterstation, approached me and asked “Do you see them?” I misunderstood and thought he said “Did you see them?” to which I answered “Yes”. He got excited and I realized what he had really said and I corrected myself. According to the Report of Air Combat dated 8 Oct 1953 submitted by the Commanding Officer, N. D. McClure, the 2 attacking aircraft made 12 firing passes. My gunnery was the only fire returned.

Of course, once we learned were under attack, we were headed for home at flank speed, probably about 170 knots. The MiGs’ broke off their attacks on us for one or more reasons. It could be that we were pulling them further and further from their base in Tsingtao and they were running low on fuel, or they were out of ammunition or perhaps they felt that with our air combat maneuvering being so successful that they would not be able to shoot us down. McGill’s assistance in spotting from the tail turret was invaluable to Mr. Hansen’s evasive action. We were lucky to be so low that they couldn’t attack from below as we had no defense from that approach. I suspect it was the elapsed time, our evasive action and possibly our finally returning fire that persuaded them to return to their base.

At any rate, we were headed for Iwakuni licking our wounds and wondering if they holed our hull to the extent that upon landing we would fill up with water and dive for the bottom. At some point near the southern tip of Korea, a USAF SA-16 Albatross amphibian intercepted us to partially escort us home and perform a water rescue if we subsequently had to ditch in the ocean. Our pilot asked the Albatross to inspect the bottom of our hull by passing back and forth beneath us to inspect for any possible damage. We wanted to know if we were damaged before landing on the water back at Iwakuni. The report was no damage seen and soon the Albatross left us thinking we could make it back OK which we did. Upon arriving at Iwakuni after our 9.9 hour flight, we were brought up the seaplane ramp immediately in case we were not watertight and to effect necessary repairs from the attack.

The next morning I went down to the ramp area to take pictures. I noted the 37 mm shell hole on the outside of the starboard vertical stabilizer was about 12 inches wide but the exit hole was perhaps some 18 inches. There were maybe 200 other holes from the shrapnel in the vertical and horizontal stabilizers and fuselage of our plane. The MiGs hit us with another 37 mm cannon shell in the port ‘beavertail’, an extension of the port engine nacelle that extended behind the trailing edge of the port wing. That shell made a perfect 37 mm hole but did not explode.

All in all, we were very fortunate that after 12 firing passes by aircraft much more heavily armed and much faster did not knock us down or even kill or injure any of us crew. One could only surmise that these Chinese fighter pilots must have been very inexperienced at air to air combat and probably very chagrined with their lack of success on that day, Oct 2, 1953!

The members of this crew not mentioned previously were LT JG H. E. Mccumber, PP1 P, LT JG J. B. Pierce, PP2P, Finady, W. H. AL2, Wald, I. M. ATAN, and Scoville, C. E. AO3.

About the Author

Dave Rinehart enlisted in the US Navy in April, 1951. Following the requisite ‘boot camp’ he was assigned to NAS Jacksonville for 8 weeks of Airman School. Then he was sent to NATTC Memphis for 28 weeks of Aviation Electronics School, graduated in July, 1952, from which he selected the aircraft carrier USS Bon Homme Richard for his first real duty assignment, knowing it was in Korean waters. The Bon Homme was conducting air strikes into North Korea three out of every four days for 30 days while ‘on the line’ with Task Force 77. While aboard the Bon Homme, he was hit by shrapnel from a 20 mm shell from a crashing F9F Panther. Thus during his brief Navy career, he was shot at twice, once by friendly fire and once by the enemy. He was only hit by the friendly!

1 Comment

Daniel Disco

August 16, 2020, 04:45Great article. I was plane captain VP 50 Crew 2 in 1960-62. The only thing I remember was 2 Russian Badgers escorting us back into our own air space. Guess we just wanted to see if anyone was watching us.

REPLY