Autor: Bob “Count” Noble Patrol squadron fifty was nearing the end of it’s 1958-59 deployment to MCAS Iwakuni, Japan. We had enjoyed successful yet typical tour, meeting our commitments without incident, and having to launch the “Ready Crew”on a rare occasion. Crew 10 had the Yellow Sea patrol on a blustery day in April 1959.

Autor: Bob “Count” Noble

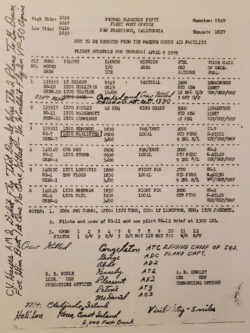

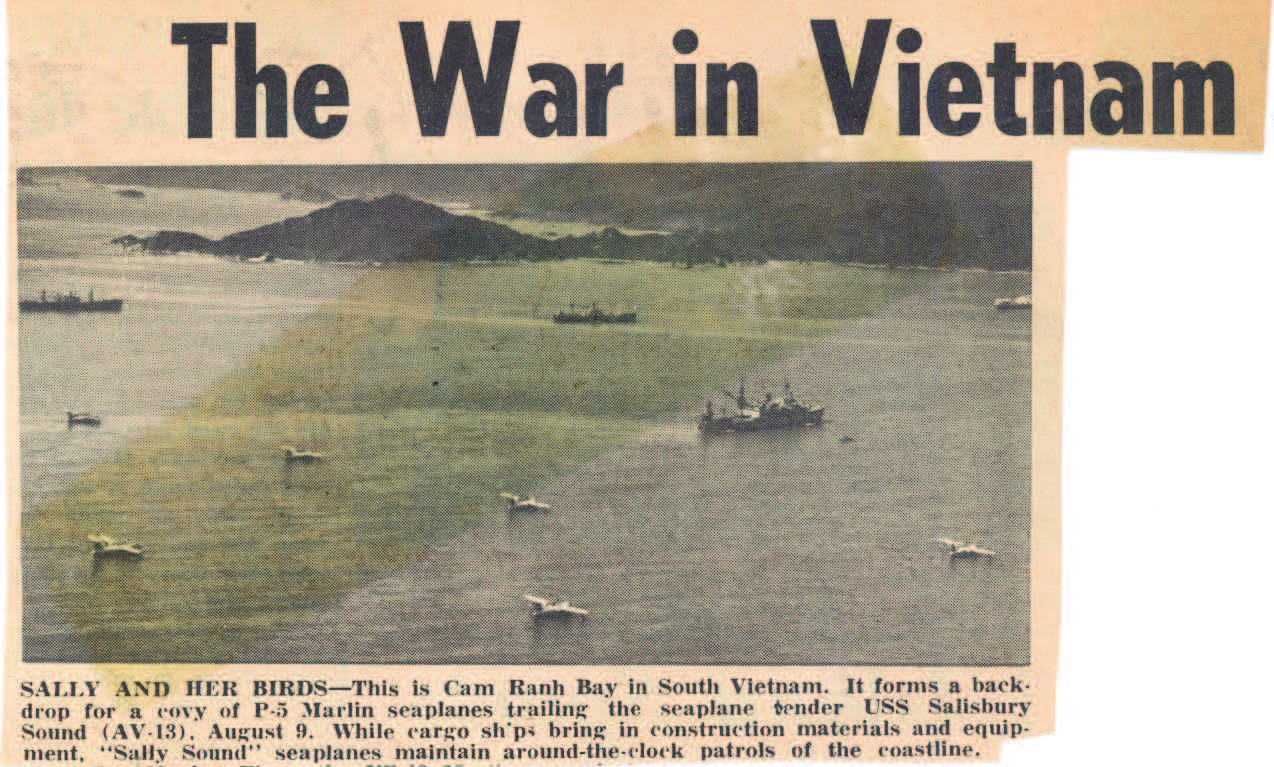

Patrol squadron fifty was nearing the end of it’s 1958-59 deployment to MCAS Iwakuni, Japan. We had enjoyed successful yet typical tour, meeting our commitments without incident, and having to launch the “Ready Crew”on a rare occasion. Crew 10 had the Yellow Sea patrol on a blustery day in April 1959. Nearing the end of their patrol they had reported “Ops normal, 33-38N, 126 11E”. That was the last contact with SG-10.

With darkness approaching and 10 boat not in sight at Iwakuni’s seadrome, Wing communications

advised the SDO that it had not received any further radio contact with Crew 10. We had to assume they were down somewhere after time of fuel exhaustion had passed.

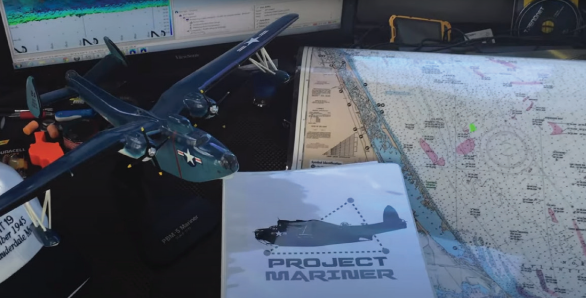

The following morning at first flight we launched a flight to back tract the planned flight path of SG-10. The M A also launched a C-118 transport to do a land search of the southern Korean peninsula. Before noon the C-118 spotted the crash site on the west face of the extinct volcano of Halla-san mountain on the island of Cheju-Do. The blackend wreckage lay about 50 feet from the top of the crater rim.

LCDR Noble, OPS Officer, Lt John Langston Safety Officer, a Corpsman and a Photographer formed the Aircraft Accident Investigation Team. A Marine C-130 flew us to Cheju-Do, landing on a dirt strip on the north side of the island at a U.S. Air Force Weather Station. Our arrival was coordinated with an Air Force chopper of an older vintage that was to lift our team to the summit of Halla-san. Loaded with its crew, our team and gear, it was unable to achieve the altitude of the summit and returned us to the airstrip at the weather station. The station OIC sergeant knew of a native guide who could lead us to the summit via an established trail on the southern face of Halla-san. Before departing we had requested helicopter support from the U.S. Army in Korea. The OIC transported the team and our equipment to a village on the south side of the island, where we met a guide and proceeded to climb Halla-san. By night fall we had climbed about two thirds up the mountain, and stopped to make a camp, eat a dinner and bed down for the night.

The following morning we were awakened by the sound of an approaching chopper, as requested, from the Army. We quickly broke camp, loaded our gear and completed the trip to the summit courtesy of the Army. Near the top of Halla-san we located a landing site about 200 feet below the rim and a half mile from the crash. The Army crew shut down prepared to stay and assist in the recovery operations. We off loaded our gear and made the easy climb to the crash scene and began gathering forensics and locating remains. Later that afternoon a local man appeared at the site with his dog. Without control, I was troubled by the thought the dog might feed on remains, so I ordered the reluctant owner and his dog to leave. When I purposely opened the flap of my .45 Colt, the native became very cooperative and departed the site.

We determined the boundaries of the crash and worked inward to the center, making note of widely spread aircraft parts and debris. The starboard engine had separated from the main wreckage and rolled about 100 yards downhill away from the crash center. The plane had pancaked onto the hillside with very little forward progress, which led us to believe there was a moment of visual contact with the ground, an abrupt “pull-up” which would have stalled the plane and resulted in a flat impact onto the hillside. The ground surface was a hillside slope of approximately 40 degrees. The hull was about 75% burned by obvious fuel fed fire, and there were no munitions carried on the mission. Parts of the cockpit and instrument panel were recovered at the rim of the crater and down a steep drop into the crater itself. Importantly, the cockpit Torque Converter instrument was recovered. At crash center we could see the frame of the starboard waist hatch door. Immediately inside the hatch we located the remains of petty officer Abdo, bent at the hips facing inboard, head down. His wallet was clearly visible in the rear pocket of his dungarees. I don’t recall the specific location of the other members of the crew, but we were confident that all hands were accounted for numerically. Their condition would require an autopsy and forensic evidence to establish the identity of each crew member.

We spent an exhausting day crawling in the underbrush, searching for bodies and instruments that would help us determine the state of the aircraft at impact. We did find the propellers, neither of which was

feathered. The port prop was located on the east side of the meadow formed by the crater about one half mile from the crash center. It was stuck in the soil by one blade, an attitude of cruciform. We were instructed to locate the radar dish, and to return with a critical element of the antenna core. It was a closely classified part of the radar system. Luckily, we dug it out of the dirt at the front of the hull. Lt. j.g. Traylor’s remains were found in the crater near the bottom of the rim. We concluded he was probably in the cockpit, or at

least on the flight deck, at impact. We camped in the crater meadow the second night.

The third day, as more of the same, finding bodies, examining wreckage, and making records and

photographs. The Army chopper was very helpful in lifting the body bags and depositing them in the

initial landing site east of the crater. On day four we gathered our belongings, crew 10, and returned to the AF Wx Sta. landing strip. The Marine C-130 returned that afternoon and flew us back to MCAS Iwakuni.

The formal investigation was convened the following day, with some guidance by the Wing Operations Officer. It was interesting how the weather had been a crucial factor in the crash. SG-10 had penetrated a fast moving cold front on its outbound track. Winds behind the front were very strong from the northwest. The Patrol track over the Yellow Sea was southerly, putting the wind on the tail and accelerating the

ground speed on that leg. It was concluded that when SG-10 arrived at the end of that leg, where a turn to the east was the intended patrol track, to fly between the southern tip of the Korean mainland and the

island of Cheju-Do. SG-10 was now set to penetrate the cold front again and a skilled pilot would climb to avoid land that probably was obscured by weather in the front. The evidence is clear that SG-10 did

climb, but equally clear that it didn’t climb high enough. The winds had pushed SG-10 about 20 miles

south of the intended easterly track. The width of the waters between the mainland and Cheju-Do is about 30 miles. The offset track was aimed squarely at Halla-san peak, elevation 6,398 feet. What an unusual altitude to fly, but another 50 feet would have clear the rim of Halla-san. Rules state that in an emergency on instruments, pilots are to climb to an altitude of 2,500 feet higher than the highest land elevation within 25 miles of the intended course. This of course did not happen. However, it begs the question, was SG-10 “climbing” to comply with the rules. The answer was determined by the torque meter, found early in the hunt for evidence at the crash site. When an instrument undergoes sudden stoppage, the needle will slap

the dial face leaving an outline of the needle formed by phosphorous on the black background. Exposing the dial to “black light” we found the reading of the gauge clearly imprinted on the dial face. As I recall it read “7”, which meant the engine was in a “cruise” setting, not “climb”. We will never know why SG-10 was at cruise at that altitude. Nevertheless, it wasn’t the proper place to be and someone had made a poor decision; conclusion, “pilot error”.

This was my first experience of filing an Aircraft Accident Report. I had hoped it would be my last, ever. The experience was unforgettable.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *